No experienced, sensitive teacher needs a curriculum for pedagogical purposes. Apprenticeship, that most ancient of pedagogical institutions, requires no curriculum. The energy spent on organizing a curriculum is cost-effective only in those situations where other things threaten the pedagogical process. For the teacher, lack of experience, of sense of pace, or of overview of the material may require generating lesson plans of such complexity and scope that they merit being called a curriculum. The need to coordinate one's teaching among students -- normally the case, if one teaches classes -- and among classes generates the need for a curriculum. This curriculum is demanded by the social environment and is written as a recognition of the threat social demands pose to pedagogical encounter. A curriculum is best understood as a conflictual document, an embodiment of the reconciliation of interests that are found in situations where teaching takes place. How adequate a curriculum is perceived to be depends upon the perspective of the person assessing it.

A curriculum serves many purposes; the three most common are: political, administrative and, supposedly, pedagogical. By a "political purpose" I mean to indicate the use of a curriculum to lay claim to the resources of an institution in competition with other claimants. "This is what we do; this is why we need such-and-such funding." A department, or school, or school district without a curriculum is handicapped in its pursuit of institutional support.

Administrative purposes tend to coincide with developmental considerations: the curriculum identifies scope and sequence so that staff, materials and space can be organized through time. Leveling not infrequently reflects some theory of learning development.

Finally, pedagogical aspects are addressed -- so far as coordination with other classes and teachers is concerned -- to the extent a curriculum identifies "units of study", be they structural, notional-functional, or whatever. The curriculum is thus, basically, an administrative aid for the teacher, rather than a pedagogical one.

Any teacher who has ever felt rushed to finish a unit to meet time or testing requirements knows that pedagogical considerations alone do not determine the curriculum. Curricula do not -- as a matter of course -- meet the needs of those individuals who are one's students. Inexperienced teachers look to the curriculum as a cookbook. But the rhythm of classroom interaction cannot be anticipated in a document never intended to anticipate that rhythm. A curriculum is a compromise of teacherly, administrative and public interests. An "ideal" curriculum which would answer all these interests simultaneously is not likely to be written in this Universe.

A curriculum sufficient to inform the laity of one's educational intents may be too vague for administrative purposes; scope and sequence organization is introduced to address the need for coordination. A curriculum adequate for administrative purposes may still be perceived to be inadequate for teaching purposes, e.g. pacing, coordinating classroom activities with texts, etc. What is an adequate curriculum? It all depends what you're going to use it for.

ESOL teachers often claim that a conflict exists between a so-called "Structural Curriculum" and a "Notional-Functional Curriculum." This is a misperception. Let us allow, for the sake of argument, that "Structural Curriculum" means something like a quasi-administrative document that organizes approaches to teaching where grammatical units are the focus and the milestones of development. A "Functional-Notional Curriculum" focuses on thematic units of some sort and treats these as its developmental milestones. (This extended locution is forced by my unwillingness to conflate pedagogical with organizational concerns.) What is the conflict? Is it a logical conflict such as, for example, one encounters in a contradiction? Is the claim that to develop a curriculum that is both structural and notional-functional is a practical impossibility?

Consider a simple chart where, the rows are named for structural items and the columns for notional- functional ones. Certainly there is no conflict here: all possibilities of combination of structural and notional-functional items can be found on the chart.

Yes, you demur, but what about scope and sequence? The simple chart is nothing more than a synchronic slice of a curriculum; it doesn't show what follows what through time.

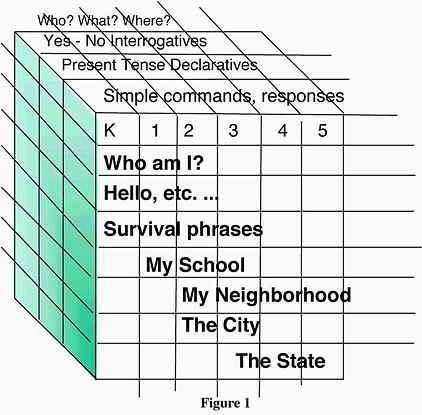

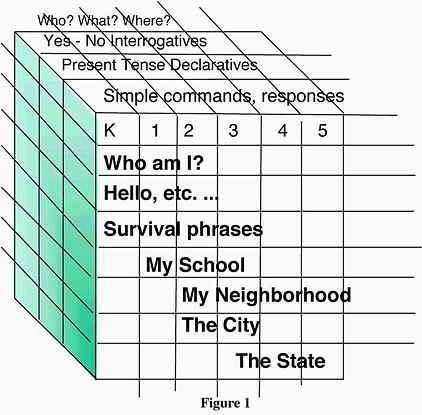

Well, then. Let's use a more complex figure. Imagine a chart on the side of a cube which across the top identified items placed in developmental sequence. For our purposes here grade levels will do, say, K to 12. Thus every column on the side of the cube represents a grade. Every row on this chart-side of the cube represents a notional-functional item. The chart so far is a fairly standard notionalfunctional curric ulum- outline.

Now, across the top of the cube up from the chart-side we order structural items. (See figure 1.) We have constructed what I will call a "curriculum project identification matrix" (CPIM, for short) a "curriculum cube", as it were.

Each bloc within the cube, cut by the planes of grade, notional- functional item, and structural item represents a potential curriculum project. There is no conflict. Of course, interior blocks could be grouped to form larger units. But each block would specify.

a. a grade (or class level)

b. a notional-functional unit, e.g. introductions,

c. a structural unit, e.g. modals.

We could now identify "curricular gaps" from the point of view of teachers who need to coordinate lessons through time and to articulate their development with other teachers or organizational processes, e.g. midterms, TOEFL's. Practical concerns might dictate grouping items, but -- theoretically, at least -- clarity exists as to what items are needed.

We can now produce a curriculum that addresses developmental, structural and notional-functional concerns. But what about other concerns, say, for addressing affective and motor skills, as well as cognitive skills? And a curriculum might also have a political dimension which defines its claims against those of other competing curricula both within and outside of the organization. How, for example, is a specific item in ESOL different from a corresponding item in the standard English curriculum? Upon such clarification does the continuance of programs often depend.

We can produce a CPIM of increasing dimensional complexity to handle all these concerns, although beyond six dimensions one is hard put to represent it in an intuitively simple way. But the logical possibilities are there. Thus we should not yield too precipitously to the despair that conflicts are insoluble.