RETURN

edited 2/10/20

The Nature of Consensus

"Getting it together"

It is by universal misunderstanding that all agree. —Baudelaire

Consensus is agreement in judgment or opinion. Disputants try to build consensus for their position among the uncommitted. Such struggles occur not only in political arenas, but also, importantly, in academic and scientific environments. This chapter explains the dynamics of consensus building and how that may influence public, or even infra-disciplinary controversies. It also provides specifics on how to evaluate consensus in three dimensions.

|

Related articles:

The Indeterminacy of Consensus: masking ambiguity and vagueness |

Democratic governments, as well as scientific disciplines, assign importance to consensus. After all, the participants, citizens or professionals ultimately must support action on controversial issues if they are to be acted on. In a pluralistic democracy, however, consensus tends to be both short-lived and shallow. It is difficult to get a diverse population to agree.

Consensus among a group of people can be evaluated in three dimensions. But let's begin with just two: breadth and depth.

1) Breadth of consensus - On a specific issue, how many members of the group agree?

For example, a great majority of people agree that, in general, traffic laws should be followed. The breadth here is substantial. Still, some exempt themselves from obeying stop signs on lightly traveled roads, others not. Many go far faster than the speed limit when it seems safe, others will obey the law even on a deserted four lane highway. So even where principle is generally honored, specific practice is open for personal decision. Thus, not only the breadth, but the depth of consensus is an important consideration. What is that?

2) Depth of consensus- given consensus on a specific issue, how many details are agreed to?

People may share consensus on a specific issue, for example, that teenage pregnancies should be reduced; but disagree when it comes to how. Some may advocate more sex education; others, the distribution of birth control devices; others, still, abstinence. Thus the initial consensus dissolves into competing proposals for action.

Depth of consensus explains much about disputes. Consider the political argumentation of elections. Citizens often complain that political candidates avoid discussing issues and overindulge in sloganizing. But savvy candidates know that slogans are a mechanism for creating consensus and that getting specific risks destroying it. Voters may agree with slogans, but usually have differing ideas on the details. (See Chapter 2 on slogans.)

We sometimes naively expect that by "getting clearer" we can resolve conflicts. People pushing for greater "clarity," greater specificity, and probing for hidden disagreements could easily undermine consensus. If we all "really" understood one another, we might disagree on even more.

For this reason, disputants spend a lot of time making issues appear "simpler" than they really are. Where commitment is unclear, obscurity is functional. Superficiality, vagueness and sloganizing in a dispute can be the means for establishing and maintaining a broad, if shallow, consensus.

"Half the work that is done in the world is to make things appear what they are not."—E. R. Beadle

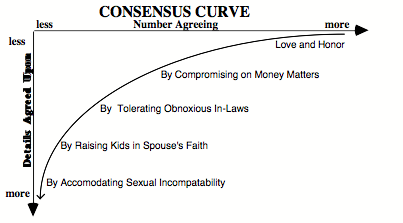

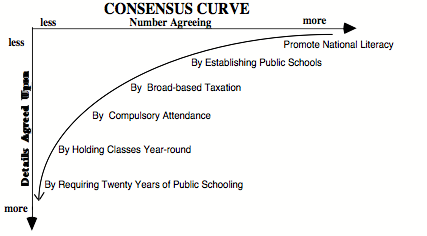

Consider a wedding ceremony. Couples vow to "love and honor" one another as their families solemnly observe. But the breadth of consensus symbolized by attendance at the marriage ceremony would probably be undercut if specifics about what "loving and honoring" mean in specific instances were made out in advance.

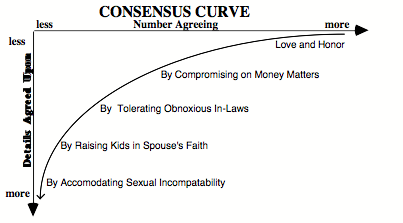

The Consensus Curve (below) shows how this works. In examining the curve notice that the slogan initially enjoys broad but shallow consensus; but fewer and fewer agree on how that should translate into action in specific instances. As we add "by" statements (by compromising on money matters, by tolerating obnoxious in-laws, etc.) more and more people in the family circle say "count me out." In the end, only a relatively narrow group of people share deep (detailed) consensus on what "love and honor" means in specific instances. Hopefully, this group still includes the bride and groom.

We can see why marital and family squabbles break out as couples try to reach agreement on the details of their initial commitment to "love and honor" one another.

Public disputes work in the same way. Consider the next figure. It illustrates consensus on the value of promoting national literacy. Notice how each specific regarding how to accomplish this goal reduces the breadth of consensus.Each new specific sparks a new dispute. In pluralistic societies in particular, breadth of consensus shrinks as we add details of implementation.

This is the critical point to understand: any elaboration of the original slogan risks creating a controversy. [1]

(Note, however, that in the sciences and in many professions, mere rhetorical manouvres can be dismissed because such groups have long traditions of methodology which may be invoked to settle controversies provided they remain within disciplinary boundaries.[2]

There is one other essential dimension of consensus. Let's call it the span. Span is a measure of how many different issues a group agrees on. Span of consensus brings up issues of priority.

Recognizing that the United States is a pluralistic society, most Americans do not find it unusual -- as many foreign visitors to the U.S. do -- that people will often live in the same neighborhood, go to school and work with others of different religions, occupations, educational backgrounds and family histories, and even with people of different ethnic and racial memberships. It is this span of consensus that defines the American pluralism.

Remember, span of consensus is different from breadth or depth of consensus. Span looks at numbers of different issues agreed on (however superficially and notes their relative priorities. Breadth of consensus looks at how many people line up on a specific issue and depth of consensus on the amount of detail they agree on.

Spans of consensus define various coalitions in the American pluralism. Knowing something about these coalitions is essential for analyzing public affairs. For instance, the Gallup organization uses the extent to which people agree on a range of values (Things like: belief in God or that America works for them.) to divide Americans into eleven distinct voter groups. Polling of these groups then allows the Gallup organization to reliably predict national election results when only a few percent of the vote has been tallied.[3]

Here is a snapshot of Gallup's basic American pluralism. You can use this table to make rough predictions of how the listed value coalitions might line up on many controversial issues. Remember, each of these groups represents a span of consensus.

Republican Oriented Groups

|

Name |

% Of Likely Electorate |

Characteristics and Typical Values |

|

Enterprisers |

16% |

Affluent, well-educated, pro-business, anti-government, worry about deficit |

|

Moralists |

14% |

Middle income, anti-abortion, pro-school prayer, pro-military |

|

Upbeats |

9% |

Young, optimistic, strongly patriotic, pro-government, worry about deficit |

|

Disaffecteds |

7% |

Middle-aged, alienated, pessimistic, anti-government and anti-business, pro-military |

Democrat Oriented Groups

|

Name |

% Of Likely Electorate |

Characteristics and Typical Values |

|

60's Democrats |

11% |

Well-educated, identify with peace, environmental and civil liberty movements |

|

New Dealers |

15% |

Older, middle income, pro-union, protectionist, pro-government |

|

Passive Poor |

6% |

Older, religious, patriotic, pro-social spending, anti-communist |

|

Partisan Poor |

9% |

Young, little faith in America or politics, worry about unemployment |

|

Followers |

4% |

Middle-aged, well-educated, non religious, non militant, pro-personal freedoms |

|

Seculars |

9% |

Middle-aged, alienated, pessimistic, anti-government and anti-business, pro-military |

Nonvoting Group

|

Name |

% Of Likely Electorate |

Characteristics and Typical Values |

|

Bystanders |

0% |

Young, poorly educated, 82% white, many unmarried, worried about unemployment and threat of war |

Gallup's data suggests that the terms "liberal" and "conservative" are of little help in understanding the complexities of public controversies. In fact, these terms are slogans that often obscure important differences among people.

Evaluate the nature of a consensus on a specific controversial issue using the following steps:

Step 1) Estimate the breadth of the consensus for the opposing sides.

A. The breadth of consensus involves a simple head count on a single issue. But anticipate that adding specificity changes the count.

B. The persistence of sloganizing and the avoidance of specifics are indicators of the proponent's belief that the consensus breadth he or she is searching for will quickly evaporate if specifics are added.

Step 2) Estimate the depth of the consensus for the opposing sides.

Remember, consensus has depth when people agree on something in detail. Thus the depth of consensus is probed by examining how many details are agreed to regarding means or ends.

Step 3) Estimate span of consensus for the opposing sides using the value coalitions identified by Gallup.

This means discarding the sloganistic "liberal" and "conservative" labels in favor of Gallup's more specific spans of consensus.

Consensus among a group of people can be evaluated in three dimensions

· The breadth of consensus, which is the number of people agreeing on an issue.

· The depth of consensus, which is the number of details agreed to.

· The span of consensus, which is the number of issues agreed on

(and on their within-group correlations of priority. See :The Indeterminacy of Consensus: masking ambiguity and vagueness ).

In general, we should expect to find that as breadth of consensus increases, depth decreases; and, vice versa. Span of consensus also decreases as details are added. This dynamic encourages superficiality and sloganizing in disputes. Perhaps a pluralistic society is possible only because people have learned to accommodate that fact that on any given issue broad consensus can be expected to be shallow.

2, Slogans 10, Nature of Society 18, Why Disputes Continue

3, Reification 16, Weighing Benefits

7, Logic of Disputes 17, Responsibility

agreement policy special interest

treaty polity contract theory

polling constituency Leviathan

Here are some controversial proposals. Refer back to the charts identifying the Gallup coalitions of interest and guestimate how different groups would line up on each of these proposals? List them in the spaces labeled "pro" and "con." What alliances form?

Also consider, what would be the breadth and depth of consensus they might share? Would it matter if more details were provided? (Provide some details yourself to further your considerations.)

1) State vouchers should be issued to help parents opt for private schooling.

Pro:

Con:

2) Drug usage should be decriminalized.

Pro:

Con:

3) Income taxes should be abolished.

Pro:

Con:

4) Laws prohibiting sexual relations with minors should be abolished.

Pro:

Con:

ENDNOTES

[1] This is an example of what is called "unpacking." See JP Redden & S Frederick (2011) Unpacking Unpacking: Greater Detail Can Reduce Perceived Likelihood. J. Exp. Psych.

[2] A very interesting presentation of several scientific controversies internal to various disciplines is presented in M. Mitchell Waldrop's Complexity. The emerging science at the edge of order and chaos. (1992) ISBN 0-671-76789-5

[3] "The People. Press & Politics," survey report for Times Mirror Corporation (September 1987). For newer versions see, for example, https://www.people-press.org/1994/09/21/the-people-the-press-politics-2/{